When selling an aircraft, conventional wisdom says that condition, hours, and maintenance history drive most of the price. But what if where you list matters almost as much as what you're selling?

We analyzed over 63,000 market observations to find out. After controlling for age, airframe hours, engine time, make/model, and interior/exterior quality, we found that location-based price premiums are statistically significant—and some states consistently command 10-15% more than others.

Here's something that should strike you as odd: if you've ever used a legacy aircraft valuation method, you've probably noticed they may not ask where the aircraft is located. They'll ask about the year, the engine time, the avionics stack, whether it has air conditioning—but not whether it's sitting in Fargo or Fort Lauderdale.

Think about that for a moment. When you price a house, location is the primary factor. A 2,000 square foot home in San Francisco costs five times what it does in rural Ohio. Even when you value a car, Kelley Blue Book asks for your ZIP code because a truck in Texas commands a different price than the same truck in Manhattan. Location-based pricing is so fundamental to these markets that we don't even question it.

Yet somehow, the aviation industry has collectively decided that geography is irrelevant to aircraft values. Major valuation guides treat a Cessna 182 in North Dakota identically to one in Maryland. The implicit assumption is that aircraft exist in some sort of frictionless national market where location doesn't matter. And of course, if you've ever bought aircraft at a distance, you know that between interstate transactions, ferry pilots, a trip for inspections, and re-basing costs, the location tax is real.

At Windsock, we don't start with assumptions about what should matter, or what would be convenient if it didn't matter—we let the data tell us what does matter. When we built our valuation models, we included location-aware fixed effects not because we assumed geography would be significant, but because it seemed worth testing.

The results were unambiguous.

After controlling for the big, measurable aircraft-specific variables like age, total time, engine hours, interior and exterior condition, and over 1,300 unique make/model combinations; state-level effects remained statistically significant at the p < 0.0001 level.

Meaning, this isn't noise. This isn't sampling error.

Geography genuinely affects aircraft prices.

The magnitude surprised us too. We expected maybe 2-3% variation between states.

Instead, we found spreads of 15% or more. On a $300,000 aircraft, that's a $45,000 difference; real money that legacy guides could leave for you to foot the bill.

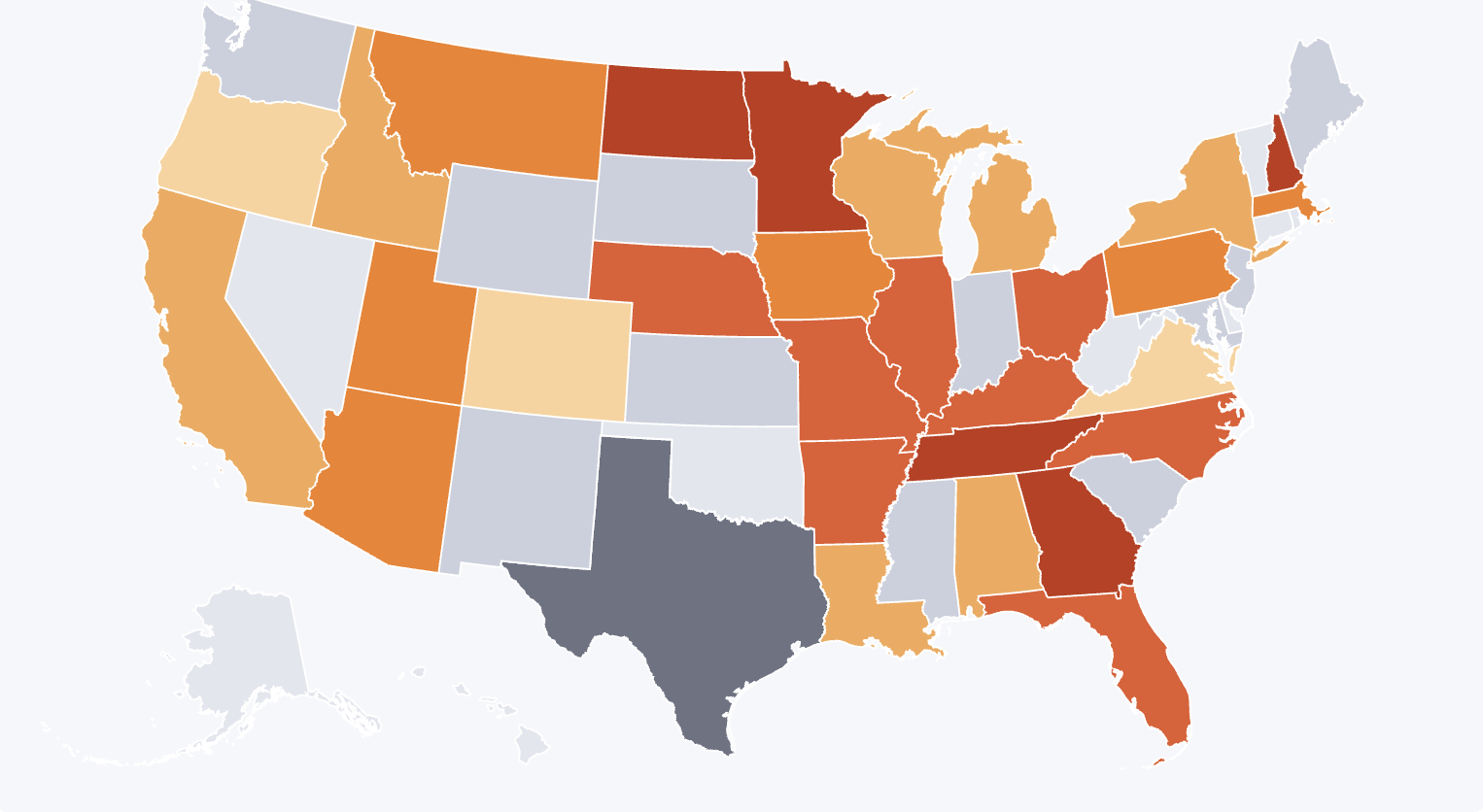

So what does the geography of aircraft pricing actually look like? The map below shows the price premium (or discount) each state commands relative to Texas, which we chose as a baseline reference state (it being big and all).

Darker oranges indicate higher premiums; grayed states have results that weren't statistically significant. The take-away? Across the country, location matters quite a bit.

The bar chart below shows every state in our dataset, ranked by price premium relative to Texas. The pattern is striking; and the spread is larger than most people expect.

Let's make this concrete. Take an A36 Bonanza; a popular six-seat single that could trade in the low-to-mid $200,000 range, for example. According to our model, that exact same aircraft; same year, same hours, same engine time, same condition scores—would list for approximately $230,000 in North Dakota but only $196,000 in Maryland.

That's a $34,000 difference. Not because of anything about the aircraft itself, but purely because of where it's located. The Maryland aircraft isn't worse. It doesn't have more hours or a run-out engine or a shabby interior. The only difference is the state line it sits behind.

$34,000 is real money.

It's an interior/exterior reboot. It's years of operating costs. It's the difference between breaking even on your aircraft and taking a significant loss. And legacy valuation guides could leave this cash on the table by not accounting for it.

The over-performing states roughly cluster in two regions: the Northern Plains (North Dakota, Nebraska, Minnesota) and parts of the Southeast (Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina). New Hampshire stands out as a Northeastern exception, possibly driven by its lack of sales tax and proximity to wealthy northeast buyers.

At the bottom end, we see Maryland, Indiana, and several states where results weren't statistically significant. Interestingly, high-population states like California, New York, and Florida land in the middle of the pack—not premium markets, but not discount markets either.

The Northern Plains and Southeast regions consistently outperform. States like North Dakota (+15.2%), New Hampshire (+13.8%), and Georgia (+13.0%) command significant premiums. Meanwhile, the Mid-Atlantic and some Midwestern states show lower or non-significant effects.

Once you see the data, the more interesting question becomes: why would anyone expect geography not to matter?

Aircraft don't exist in a vacuum. They exist in local economies with dramatically different characteristics.

Economic conditions vary enormously. Median household income in Massachusetts is nearly double that of Mississippi. Discretionary spending on aviation; whether for business or pleasure tracks with regional wealth. Areas with more high-net-worth individuals have more buyers competing for desirable aircraft, which naturally pushes prices up.

Operating costs differ by location. Avgas prices can vary by $2-3 per gallon across the country. Hangar rents range from $200/month at rural strips to $2,000+/month at congested metropolitan airports. Annual inspection costs, insurance rates, and maintenance labor rates all have geographic components. An aircraft that's cheap to operate in one region may be expensive to operate in another—and buyers price that in.

Tax treatment varies wildly. Some states have no sales tax on aircraft purchases. Others impose the full state rate. Some offer fly-away exemptions; others don't. A few states have aggressive use tax enforcement that effectively adds 6-8% to the cost of importing an out-of-state aircraft. Smart buyers know this and adjust their offers accordingly. A premium-state aircraft may actually cost less net of taxes than a discount-state aircraft once you factor in the tax hit.

Buyer demographics differ. Some regions skew toward working aircraft used for business, ranching, or transportation in areas with limited road access. Others skew toward recreational flyers. Business buyers often care more about capability and dispatch reliability than price; recreational buyers may be more price-sensitive. The mix of buyer types affects market-clearing prices.

Local aviation culture matters. Some states have strong GA communities, active flying clubs, and well-maintained infrastructure. Others have seen decades of airport closures, restrictive regulations, and dwindling pilot populations. Areas where flying is thriving tend to have healthier markets.

So why do existing valuation methods ignore all of this?

One explanation is that traditional valuation guides were designed in an era of limited data. When you're working from pen-and-paper style models, there's not enough statistical power to detect regional effects. It's just easier to publish one national number than to try to estimate fifty state-level adjustments.

The other possible explanation is inertia. The aviation industry moves slowly. Valuation guides that were adequate in 1985 get grandfathered forward because "that's how we've always done it." Brokers and lenders build workflows around existing methods. Nobody wants to be the first to rock the boat.

But the result is systematic blind spots. Sellers in premium states may not realize their aircrafts full value because their valuation guide says the aircraft is worth less than the market will bear. Buyers in discount states overpay because they're anchored to a national average that doesn't reflect local conditions. Brokers in both scenarios give advice that's well-intentioned but empirically incomplete.

This is a solvable problem. We have the data. We have the statistical methods. We can measure geographic effects with precision. The only question is whether the industry is ready to update its mental models.