Here at Windsock, we're reinventing aircraft valuations from the ground up - we're ditching the statistics 101 model to shape the next generation of our industry. And one of the longest held industry superstitions surrounds avionics: namely, that the value of an avionic is equal to its price.

What do we mean by that? When old-school players price out an aircraft, they assume that the value of an avionic, say a Garmin GNS-430W, applies the same to every aircraft: $5,000 in a Skyhawk, $5,000 in a Baron, $5,000 in a King Air, and so forth.

While an avionic may be the same price when ripped out of the panel, it has a distinct, contextual value to the market when installed in a particular aircraft. Intuitively, that singular price approach is obviously wrong - and now, we're happy to provide the industry with the receipts to prove it.

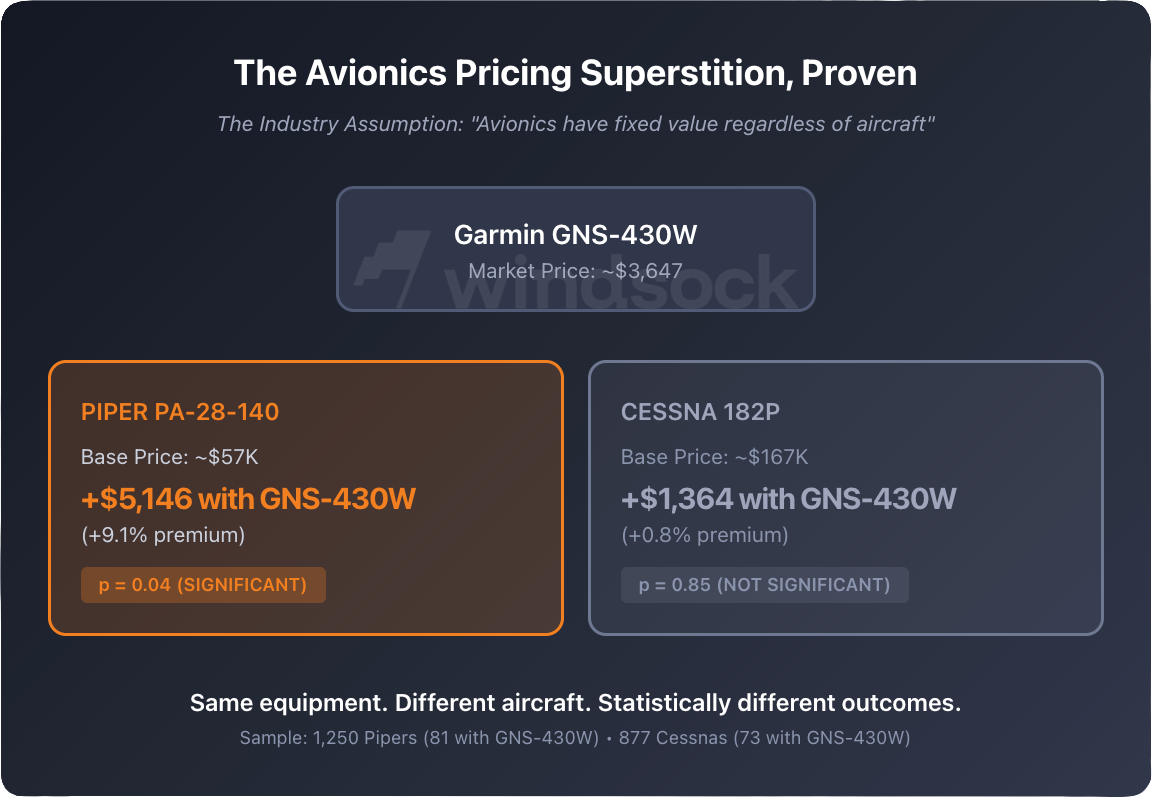

A Garmin GNS-430W installed in a Piper PA-28-140 Cherokee, statistically, adds about $5,000 to the aircraft's value.

Install that same unit in a Cessna 182P Skylane? It adds nothing to the aircraft's value.

Not "less." Nothing. The price difference between Skylanes with and without this avionics package is indistinguishable from random noise.

How do we know that? We took two popular aircraft frequently on the market, frequently equipped with GNS-430W's, but serving two distinct parts of the market - entry level and intermediate / high performance. Our expectation would be that entry level aircraft have lower market expectations, and as a result, a GNS-430W would have a stronger differential effect on value than the aircraft up-market. We looked at 1,250 PA-28-140s and 877 182Ps that have been on the market over the past decade to ask: how much does the value change when a GNS-430W is aboard?

If you wanted to test whether avionics have uniform value across aircraft types, you'd design exactly this natural experiment:

Same era, same market segment. Both are single-engine piston aircraft from overlapping production years. Both are among the most popular aircraft ever built—no weird sample size issues, no niche market dynamics.

Same equipment. The Garmin GNS-430W is one of the most common GPS/NAV/COM units in general aviation. Thousands installed, well-understood capability, and a liquid secondary market.

Different price points. In our sample, the Cherokee averages $57K; the Skylane averages $167K. If avionics value scales with aircraft value, we'd see proportional premiums. If it's fixed, we'd see identical dollar premiums. If it varies by context—well, that's what we're testing.

This natural experiment provides the perfect dataset for testing our hypothesis - does the legacy valuation industry get avionics values wrong?

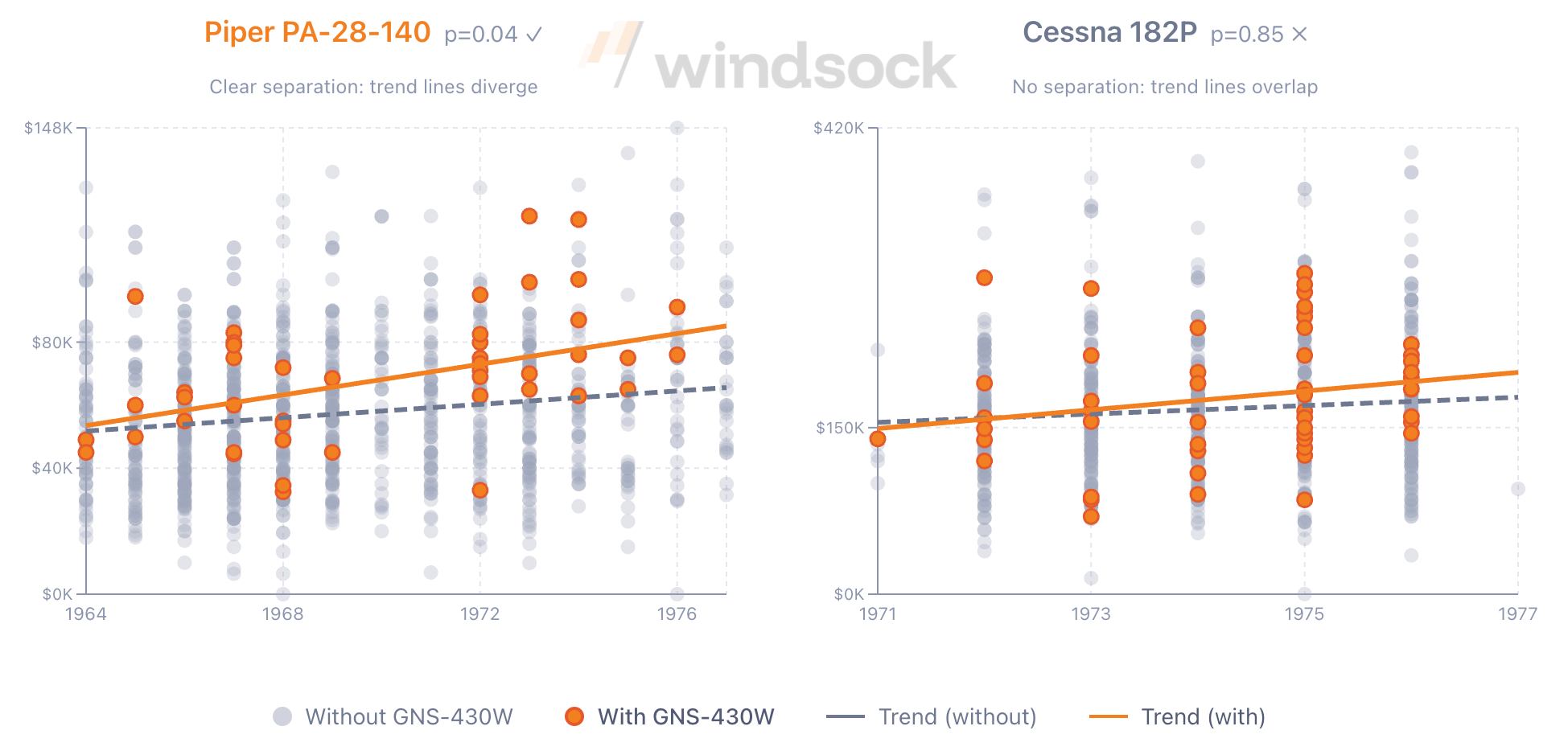

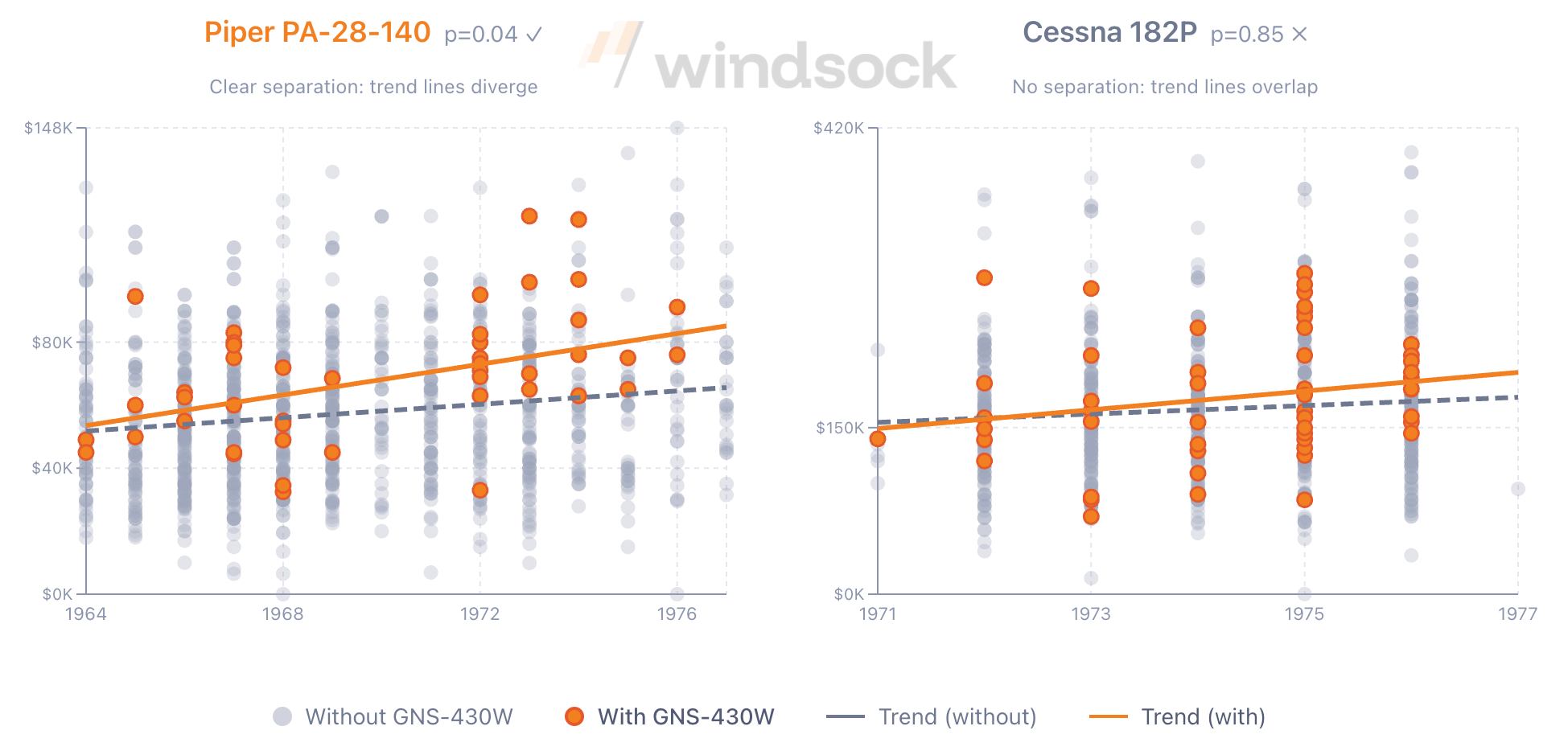

This chart tells us everything we need to know - with the Piper PA-28-140 market, the aircraft with the GNS-430W equipped are consistently on the higher side of the market (i.e. orange dots tend to be higher up in the yearly price spread), while with the 182P market, they're right down the middle. Visually it looks real, but what do the stats actually say?

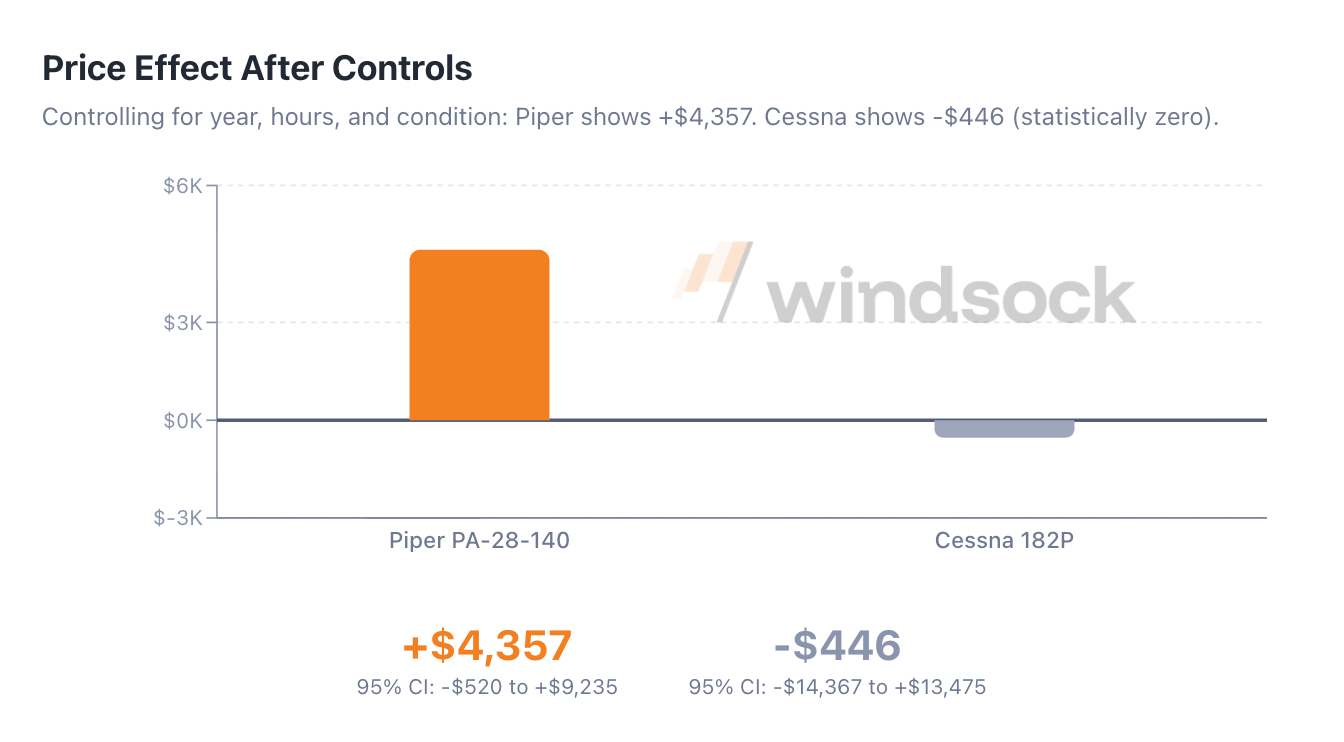

Statistical analyses can be fragile. A result that appears in one test might vanish in another. So we threw four fundamentally different methods at this question:

Simple averages: Are prices higher with the avionics? (Piper: yes, p=0.04. Cessna: no, p=0.85)

Distribution comparison: What if prices aren't normally distributed? Compare rankings instead. (Piper: yes, p=0.03. Cessna: no, p=0.68)

Controlled regression: What's the premium after accounting for model year, airframe hours, and condition? (Piper: +$4,357. Cessna: -$446, statistically meaningless)

Percentage impact: What percentage premium does the avionic command? (Piper: +13.3%. Cessna: +0.1%)

Four tests. Four methodologies. And yet, the same answer every time. When every analytical approach points in the same direction, you're not seeing a statistical artifact. You're seeing reality.

Once you see the data, the "why" is obvious:

Skylane buyers expect capable avionics. At $167K, you're expecting a serious IFR capable platform. A GNS-430W meets expectations; it doesn't exceed them. Buyers won't pay extra for table stakes.

Cherokee buyers might not. At $57K, you're often buying a trainer or first airplane. Many are VFR-only. A GNS-430W transforms capability—suddenly you have real IFR equipment. That upgrade is worth paying for.

Relative investment matters. A $3,600 radio is 6.4% of a Cherokee's value but only 2.2% of a Skylane's. Same hardware, very different context.

This isn't exotic economics. It's common sense. The surprising thing isn't that avionics value varies by aircraft—it's that the industry pretends it doesn't.

The aviation industry operates on an implicit assumption: avionics have fixed market value regardless of aircraft type.

Traditional approaches treat a GNS-430W as worth the same whether it's in a Cherokee or a Cirrus.

In logic, disproving a universal claim requires only one counterexample.

"All swans are white" falls the moment you find a single black swan, and with this data driven market example, we have that black swan.

We didn't use obscure aircraft or exotic equipment. The PA-28-140 and Cessna 182P are mainstream. The GNS-430W is ubiquitous. If uniform pricing fails here; with common aircraft, common avionics, and plenty of transactions, it likelyfails everywhere.

The industry assumption isn't approximately right.

It's demonstrably wrong.

The only question is how long valuations will keep pretending otherwise.

Analysis: 2,127 aircraft (1,250 PA-28-140s, 877 182Ps). Statistical methods include t-test, Mann-Whitney U, OLS regression, and log-linear regression.