For decades, aircraft valuation has been based on what we like to call Statistics 101 thinking. The method, at a high level, is simple: take the aircraft listings you can find this quarter, toss out the outliers, average the rest, and call that the market value. It feels simple and reasonable.

But simple isn’t the same as accurate.

In aviation, this approach falls apart because our market just doesn’t behave like real estate or the stock market. Aircraft don’t sell every day, and no two planes are identical.

Economists call this kind of environment a thin market. It means there aren’t enough transactions for the averages to work the way the textbook says they should. When you try to apply traditional statistics to a thin market, you don’t get “slightly fuzzy” results. You get systematic errors that look scientific, but we think are fundamentally wrong.

To put this to the test, we tracked five Cirrus SR22 aircraft continuously from late 2020 through late 2025 against a rolling 90 day window of all Cirrus SR22 aircraft on the market throughout that period.

How well does the average price in that window actually reflect the value of those planes over time?

We believe machine learning isn't just better for aircraft valuation - it's the only approach that can actually work. Let’s walk through the damage a thin market can do to statistical analysis.

Here’s what we found: the so-called market average swung from $263,000 up to $644,000, then back to around $546,000. That’s a 145% swing!

Did SR22 values actually double and then drop by almost half?

Of course not.

The real aircraft values changed gradually and predictably, appreciating between about 10 and 38 percent over that same period. The wild swings weren’t real market movement. They were a reflection of which aircraft happened to be listed that quarter - sometimes, the aircraft were just nicer, sometimes they were rougher - and in a thin market, those small fluctuations cause real damage.

This is what happens when you apply Statistics 101 to a thin market. The data looks official, but the “signal” is mostly just noise.

Traditional valuation methods have to pick between three equally bad options when choosing how much data to use in a thin market.

If you want enough listings to make your averages “statistically valid,” you have to include data from a long timeframe. But aviation markets move faster than that. Interest rates change, fuel prices spike, and ADs change the value landscape. By the time you’ve collected enough listings, you’re describing last year’s market, not today’s.

If you only use recent data, you capture the current market. But now you have hardly any observations to work with - we’re back to the thinness problem. Many aircraft types see only a few transactions per quarter. Averaging two or three sales isn’t real statistics, it’s a hunch.

You could try to find a balance. Maybe six months for one type, three for another, weighting recent data a little more. But at this point, you’ve traded mathematical bias for human bias about how to weight each part of the market manually. You’re not fixing the problem. You’re just guessing in a slightly different way.

There’s no way out of this tradeoff using traditional techniques. It’s like being stuck in a valuation coffin corner. Too slow and you stall, too fast and you break the model. There’s no stable flight envelope left.

Instead of all those manual patches with Option 3, you may decide to make some rules about how to do it without introducing bias. Maybe some prescribed adjustment for engine hours, perhaps an adjustment for every increasing model year, or standard rules for all accidents. Congratulations, you’ve just invented a simple model, also known as linear regression.

And if you’re going to model anyway, you might as well do it properly.

Because markets aren’t linear. For starters, accident effects aren’t linear, and even simple seasonality has a real market effect.

A 2010 aircraft model might appreciate faster than a 2015 aircraft model depending on equipment, hours, or location. Once you start adding factors like avionics upgrades, total time, or condition ratings, the math quickly becomes too complex for hand-built equations.

That’s where machine learning comes in. It doesn’t need to assume the market moves in a straight line. It can learn the relationships between all these variables simultaneously, without the arbitrary tradeoffs that traditional methods force you to make.

In thin markets like aviation, several needs directly conflict:

These demands contradict one another. You can’t satisfy them all using averages. That’s why old-school statistics simply cannot produce consistent, unbiased valuations for aircraft markets.

We believe the only viable way forward is to use models that learn general relationships between aircraft features and value, and then apply those relationships to estimate specific aircraft prices.

In other words, to graduate from Statistics 101 to Statistics 2025.

The Cirrus SR22 is one of the most traded piston aircraft on the market. It’s about as “liquid” as aviation gets, with an average of 146 listings per 90-day period. That makes it the perfect test case. If traditional methods worked anywhere, they would work here.

They don’t.

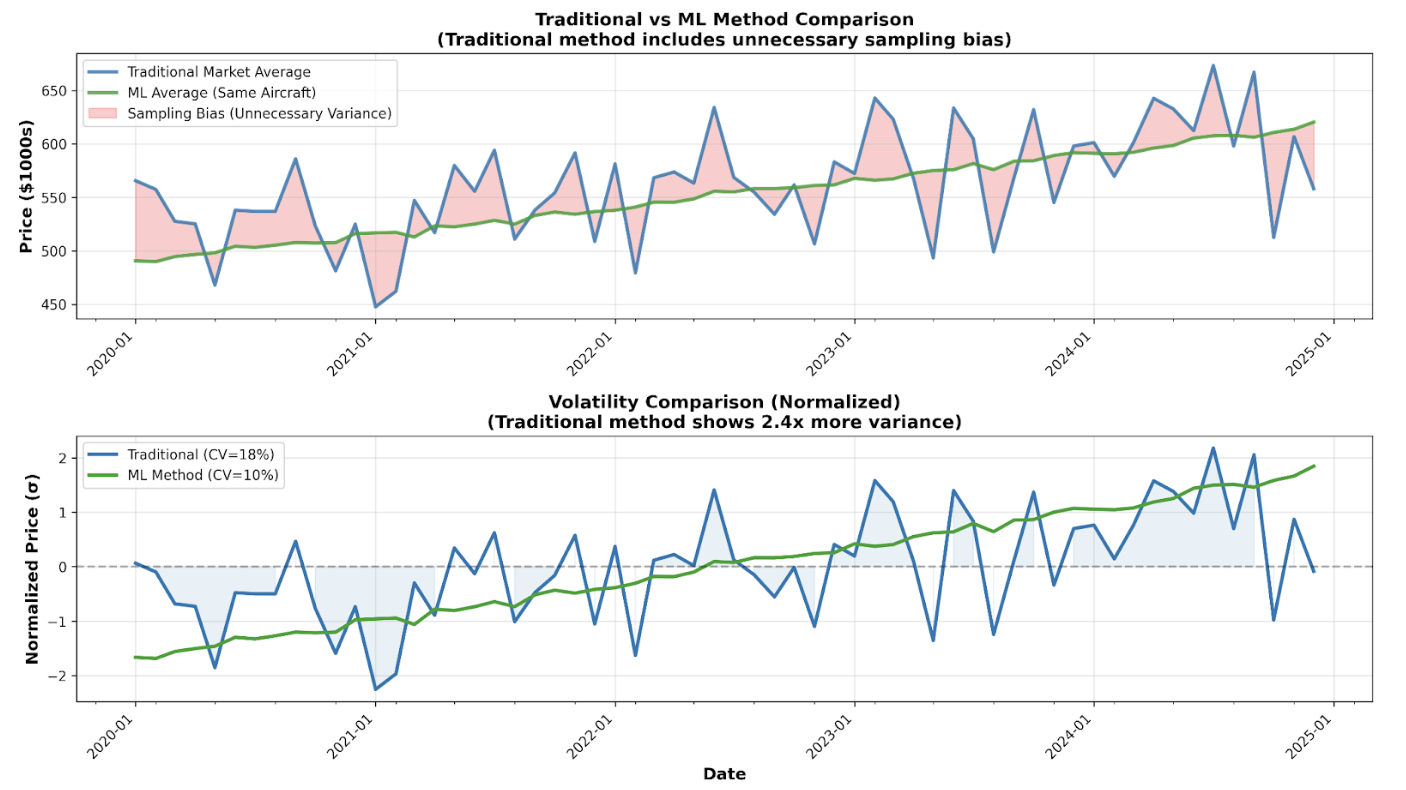

A typical traditional average produced a 17.9 percent coefficient of variation, meaning its valuations bounced around nearly 18 percent from one period to the next. The machine learning approach produced a much steadier 10.6 percent variation. That’s 40% less noise in the results.

In plain language, that means a typical SR22 valued around $490,000 could be off by about $88,000 using traditional methods, versus about $56,000 using machine learning. Nearly $32,000 of that difference is just sampling error, not real market change.

And remember, that’s in one of the healthiest, most active markets in general aviation. For rarer aircraft like King Airs or vintage warbirds, the picture is likely much worse.

It’s tempting to think of machine learning as a high-tech add-on. But in thin markets, it’s not optional. We believe it’s the only mathematically coherent way to handle the data.

Modern models like Windsock can do several things traditional statistics can’t:

When we tracked our five SR22s over five years, each one showed a variation of roughly 9 to 12 percent, depending on age and condition. That’s a realistic reflection of actual market dynamics, not random listing noise.

This isn’t just a fancy statistics argument.

The cost of bad valuation methods ripples across the entire aviation economy.

When banks rely on valuations filled with 59 percent noise, they either take on unnecessary risk or demand extra collateral. That means fewer loans with worse terms for owners.

When insurance companies use inflated volatility estimates, premiums rise for everyone.

When buyers and sellers negotiate using price ranges that swing hundreds of thousands of dollars, deals fall apart that shouldn’t.

Across thousands of transactions, this adds up to millions in wasted or misallocated capital every year. The math doesn’t just affect spreadsheets. It affects who gets to buy, sell, and fly.

Traditional valuation methods made sense back in 1985. You didn’t have access to big datasets or modern computing power. Averaging listings was the best you could do. But we’re not in 1985 anymore.

Today, machine learning is used to predict the weather, detect medical conditions, and power every major pricing system from Uber to Zillow. There’s no reason aircraft valuation should still rely on the mathematical equivalent of a sundial.

The question isn’t whether machine learning is “better.”

The question is whether traditional methods can provide the intelligence the market demands. Our research suggests they can’t.

Now we have better tools. It’s time to use them.

The SR22 study was the most optimistic scenario for traditional methods: high production volume, plenty of listings, and relatively stable pricing. Yet even here, the results show:

If that’s the best case, imagine how wrong the numbers could get for rare or unique aircraft.

Aviation markets are thin, dynamic, and complex. That means Statistics 101 no longer applies. You can’t just average a few listings and call it truth.

It’s time to move forward with Statistics 2025, where models don’t just average the market, they understand it.

Give it a try, sign up for free and run a Windsock aircraft valuation report.